The Inner Loop

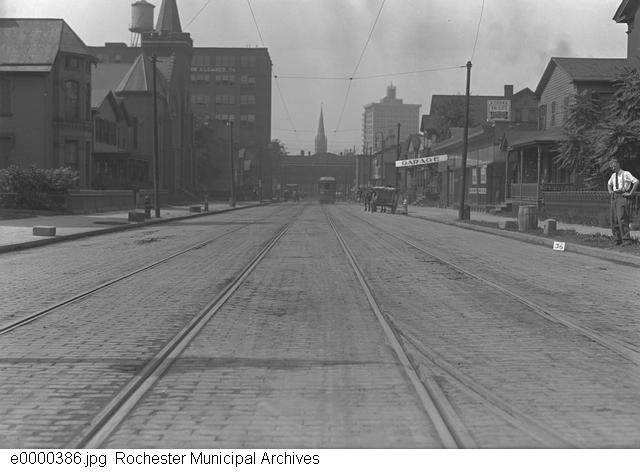

The mid-twentieth century saw the transition from rail transit to automobiles. The growth of highway culture across the United States led many cities to construct sunken and flyover multi-lane expressways around and through their downtowns to avoid congested streets and to move people from the suburbs to downtown without having to pass through the outer neighborhoods. The popularity of these expressways in the 1950s meant that there was federal funding available for their construction. Rochester took advantage of this to create its own sunken expressway that encircled the business district of Rochester, called the Inner Loop.

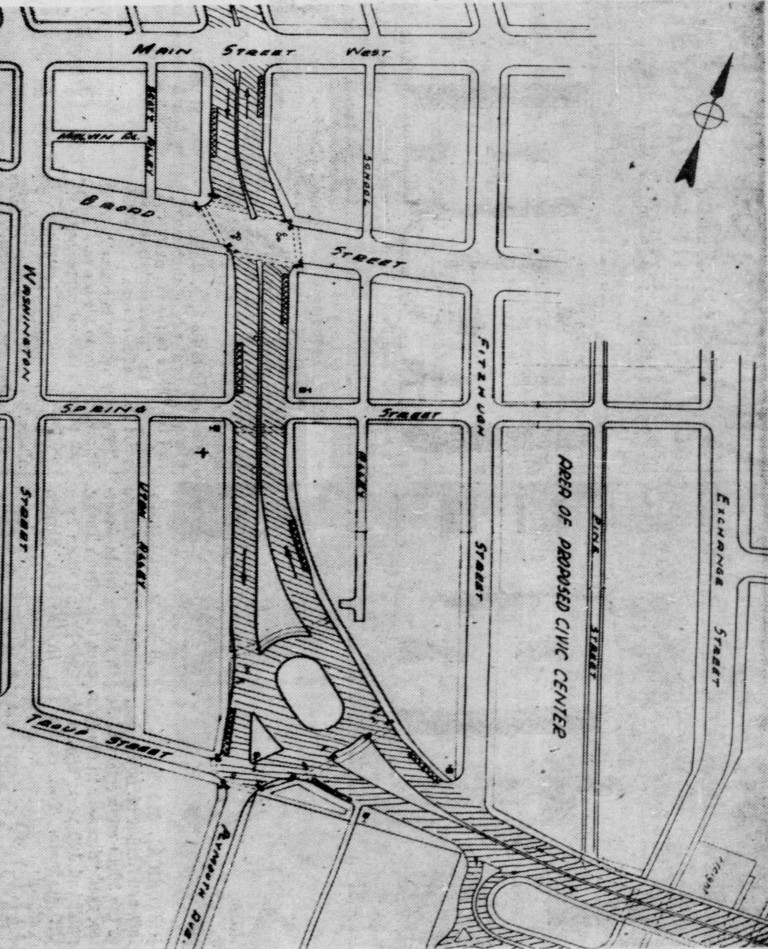

The path of the modern Inner Loop over the Plat Map from 1935-1936.

The Inner Loop was originally constructed in five sections between 1952 and 1965 with subsequent alterations and expansions. The first arc to be built was the 0.47 mile long stretch along Central Avenue to Allen Street and then down North Plymouth Avenue to West Main Street with Plymouth Avenue acting as the western boundary for the Inner Loop until 1971 when it was expanded to its modern route.

The Inner Loop today with arcs marked by completion date.

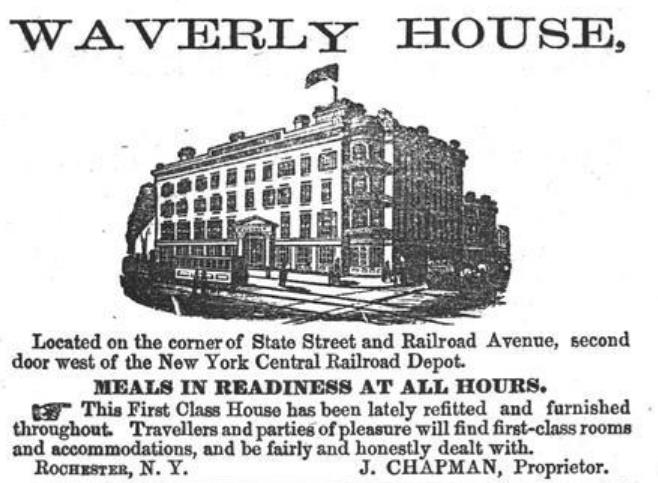

Demolition along this arc began in the spring of 1952. Most of the structures along this stretch were very old and had to be dismantled brick by brick, a painstaking process that could take days, even weeks. Though mostly a residential neighborhood, there were some historic non-residential buildings that were razed. The oldest of these was the Savoy Hotel, a 125-room inn on the corner of State Street and Central Avenue, close to the train station. Built in 1848, this hotel was originally called Waverly House and boasted Buffalo Bill Cody as a one-time guest, though they more famously denied service to one of Rochester’s most famous residents, Frederick Douglass, in 1872. Like the passenger train station that provided most of its customers, the Savoy Hotel declined through the early twentieth century.

Another building that was lost was the First United Presbyterian Church, which had been in that location since 1849. After the destruction of their church to make way for the Inner Loop, the displaced congregation moved to the town of Gates. In addition to the mixed-use buildings in this neighborhood, the section of Central Avenue west of St. Paul Street was also destroyed to make room for the Inner Loop. This first arc of the Inner Loop was completed in 1953.

Construction on the second arc began that same year. Here, the Inner Loop continued along Plymouth Avenue south of Main Street and then curved along Troup Street in the Corn Hill neighborhood before ending at the Genesee River. This section of the Inner Loop that no longer exists in its original form, but was expanded in 1971.

Before construction could begin on this section, the demolition of over thirty buildings was required. Several of the buildings that were razed were apartment buildings along South Plymouth Avenue, namely, the Columbia, the Hilton, and the Casa Loma, forcing the tenants to find housing elsewhere.

As with the first arc, the construction of the second arc also required the destruction of several non-resident buildings. Some of these were long-standing and well known shops: Granger Radio Service, Levin Painting, and Wolford’s Books and Fine Arts. Wolford’s in particular was housed in what was reported to be the oldest standing residence on the west side of the city. Constructed between 1821 and 1823, its former lot now contains the parking lot for the Monroe County Jail.

Anther buildings that was removed the Lewis Henry Morgan House. Lewis Henry Morgan, who had lived at 124 South Fitzhugh Street, was an anthropologist, social theorist, and lawyer and his home was a “hub of intellectual activity in the nineteenth century” according to Emily Morry of Rochester Public Library’s Local History Division. In 1938, the Morgan House was given an historic marker from the New York State Education Department at the behest of the Rochester Historical Society for being the location where leaders first outlined their demands for co-education for the University of Rochester. Despite its significance and long history, the Lewis Henry Morgan House was torn down in 1953 to make way for the Troup-Howell bridge, which brought the Inner Loop across the Genesee River.

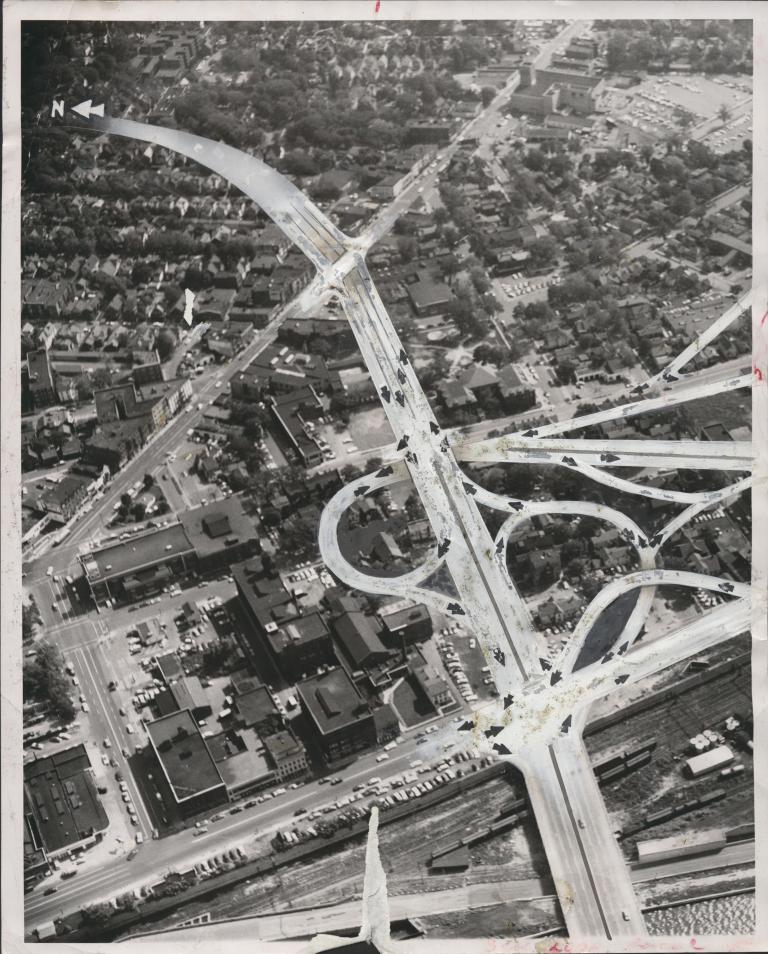

The third arc of the Inner Loop was the first to be constructed on the east side of the Genesee River. Continuing from the second arc, it ran from the Troup Howell Bridge along Howell Street to the corner of Union Street and George Street. This half-mile arc ended up being the most expensive and the most complicated of the five sections, completely changing the face of the 4th Ward.

Demolition in this neighborhood began in the fall of 1955. Over 160 structures were razed to make way for the Inner Loop, including family homes and apartments as well as commercial property, forcing many people to leave their homes and find living and business space elsewhere. Among these were Rabe’s Complete Auto Service, originally founded in 1893 as a harness company, and Carhart’s Photo Service and Camera Shop, a family owned business founded in 1914 that had become the largest developer in Western New York.

It looks like Coventry after the blitz

Arch Merrill, Democrat & Chronicle (1956)

In addition, almost every building on Howell Street, Marshall Street, Griffith Street, South Avenue, and Byron Street were razed. Several streets themselves were also severed or completely removed. Marshall and Griffith Streets, which had originally run from South Avenue all the way to Monroe Avenue, were cut short at Clinton Avenue. Howell Street, which had also run from South Avenue to Monroe Avenue was all but destroyed and George Street no longer exists. In 1956, Arch Merrill, a writer for the Democrat & Chronicle described the scene with horror, saying, “where loop demolition is underway at the eastern end of the new bridge, it looks like Coventry after the blitz.” Work on this section was completed two years later in 1958.

The fourth section of the Inner Loop was the most destructive of the five and required three years of demolition before construction could begin. This nearly mile-long stretch of neighborhood ran from Front Street to North Street along Cumberland Street. Over 250 commercial and residential buildings were destroyed in the densely populated mixed-use area, including four blocks worth of businesses near the New York Central Railroad Station, which a pro-Inner Loop article published in the Democrat & Chronicle in 1957 described as “architectural monstrosities and crumbling fleabags.”

These crumbling fleabags included the Railroad YMCA at 9 Hyde Park Street which was demolished in the fall of 1957. Originally built in the early twentieth century, the Railroad YMCA offered room, board, and entertainment to transient railroad workers passing through the city. As the century wore on, its use diminished until it was converted into a general boarding house two years before its demolition. Another of the businesses that was demolished was the Hotel Gilliard. Founded in 1886 by Valentine Gilliard, a German immigrant, this hotel boasted twenty rooms and a tavern on the ground floor. This establishment continued to function as a hotel even after it wa sold by Gilliard’s family after his suicide until it was claimed by the state in 1957 for demolition.

In addition to buildings, this arc of the Inner Loop also required the destruction of Franklin Square, one of the city’s oldest parks. Founded in 1826 between Cumberland Street and Andrew Street, Franklin Square hosted amateur baseball games in the 1850s and 1860s and later became the site of many political demonstrations. Franklin Square was also the home of Rochester’s Spanish-American War Memorial by sculptor Carl Paul Jennewein. To make way for the Inner Loop, the northern section of the park was removed. This included the area with the memorial, which was moved to the Community War Memorial, now the Blue Cross Arena. With demolition complete, construction began in 1960 and this section was finished by 1962.

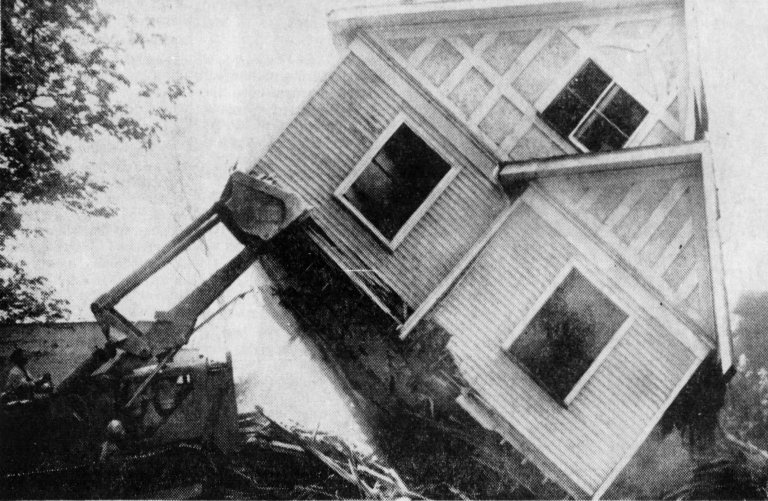

The final arc of the Inner Loop was completed in 1965 and stretched from Scio Street to the intersection of Union Street and George Street. Although less destructive than the previous section, this fifth arc still required the demolition of many homes and apartment buildings, one of which was 72 Joslyn Place, whose removal provides one of the most extreme examples of the popular unhappiness with the forced evictions and removals.

72 Joslyn Place was an apartment building slated for demolition along with the rest of the street. It was the home of Mrs. George R. Woods, who lived there with her son and her dog. The residents of 72 Joslyn Place received notice of the building’s demolition in 1962 at the same time as the landlord stopped collecting rent. By March of that same year, all of the utilities had been removed and most of the residents had vacated and moved elsewhere. All but Mrs. Woods and her son. Dressing warmly against the cold and getting water from a nearby hydrant, Mrs. Woods held off the landlord and later state agents by telling them that she was just waiting on the moving company. Mrs. Woods and her son refused to leave although the rest of the street had since been demolished, but in May of 1962 they finally gave into the pressure to leave. Although not a common reaction to the forced evictions and demolitions, the story of Mrs. George demonstrated the general mood of those being asked to leave their homes to live elsewhere for the sake of the Inner Loop.

Every day the genius of this loop concept becomes more apparent

Democrat & Chronicle (1961)

Although those being removed were less than pleased with the creation of the Inner Loop, others viewed its construction as a benefit to the city. In March of 1961, four years before the Inner Loop’s completion, an article was published in the Democrat & Chronicle that stated, “We look at the loop now – the finished part of it – and we use it with the realization that Rochester would be literally choking to death on traffic without it. Every day the genius of this loop concept becomes more apparent.” Others, businessmen in particular, looked on the destruction caused by the Inner Loop as the unfortunate price of progress and viewed the Inner Loop, once completed, as a success. Rochester District Engineer Bernard F. Perry called the opening of the Inner Loop “One of the most important days in the history of Rochester and Monroe County.” He continued, saying, “We are extremely proud of this achievement, the result of long planning, intricate design and elaborate construction.” Byron Johnson, the president of the Chamber of Commerce agreed, adding that, “Without businessmen willing to support it, this Inner Loop might have become a useless noose around a deserted central area.”

This positive outlook did not last. By the end of the twentieth century, leaders and residents had begun to notice the, as Norman Garrick put it, “devastating effect urban freeways have on downtowns across the U.S.” The presence of a sunken highway circling downtown had stagnated the hemmed in businesses while making the city’s outer neighborhoods inaccessible to the city center. Former Mayor Lovely Warren described it as a moat that separated downtown Rochester from its neighborhoods. Others described it as a noose strangling the city. It was determined that something needed to be done to revitalize downtown Rochester and undo some of the harm done to Center City and the surrounding neighborhoods by the construction and presence of the Inner Loop.

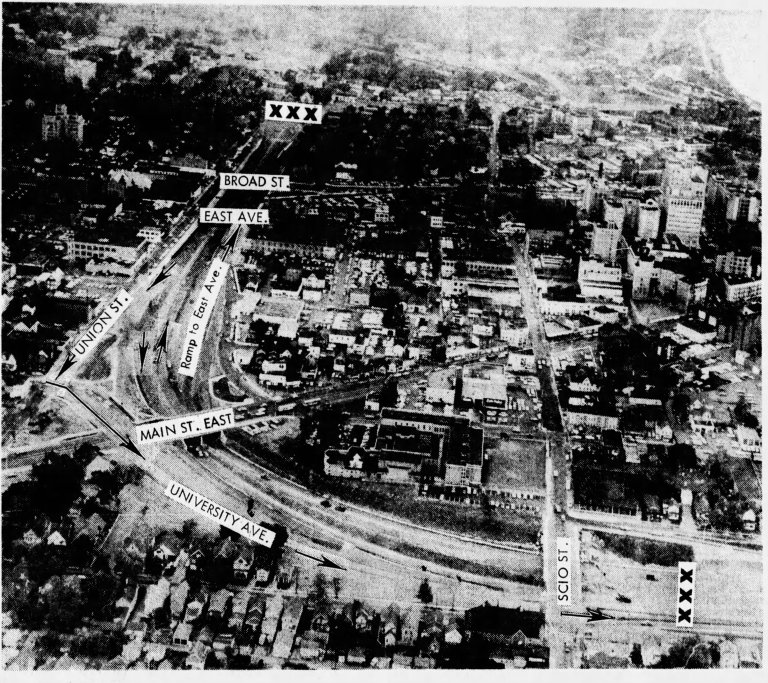

The Inner Loop East Project was conceived to fill in the sunken fifth arc of the Inner Loop and turn it into an at-grade “complete street” that included walking and bike paths and mixed-use developments. This project was first planned in 1999 in “Rochester 2010: The Renaissance Plan” which was quickly followed up with the 2001 Inner Loop Improvement Study, a traffic study for which the city had been awarded a small grant. It was determined that this section of the Inner Loop saw very little traffic in particular, no more than a moderately busy two-way street and certainly not enough to warrant the maintenance of an expressway.

Studies done elsewhere added to the evidence that removing pieces of the Inner Loop would be beneficial to the city. Studies had shown that cities with built up or sunken expressways, parking lots, and single-use buildings lost walkability and created traffic influxes even as people moved out of the city. It was also found that cities that removed their expressway, something that usually occurred due to natural disasters, saw a drop in traffic congestion. Taken together, this was the information that was needed to move forward with the Inner Loop East Project.

The remainder of the decade was spent obtaining the funds necessary to complete the project. In 2005, Congresswoman Louise Slaughter led the first effort to raise funds which resulted in a $2.5 million grant that was used for the preliminary design of the infill project. A few years later, the city received a TIGER Grant from the United States Department of Transportation for over $17 million.

With the grant money and other funds raised by the city, the project got underway in 2014. The “First Fill” Ceremony was held on November 14, 2014 and was hosted by Mayor Lovely Warren and attended by Senator Chuck Schumer and Congresswoman Louise Slaughter. By 2016, the entire eastern section of the Inner Loop was gone, and by the end of 2017, the project was completed, and Rochester had an at-grade boulevard with parcels of land awaiting mixed-use development.

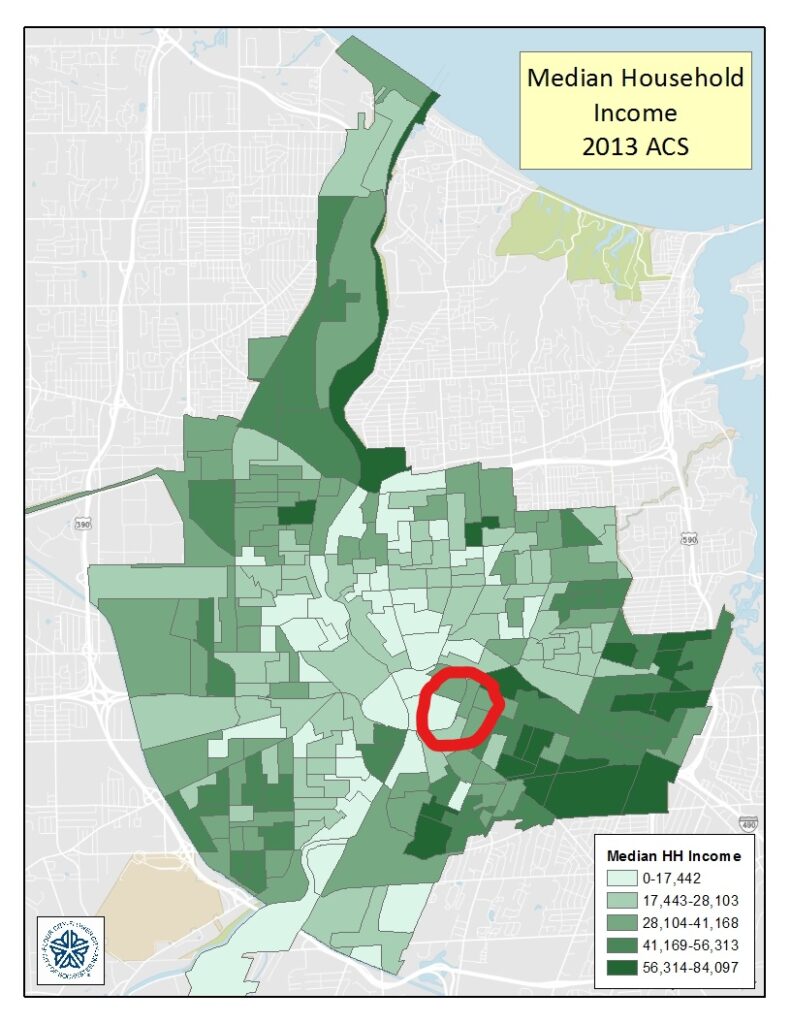

Today, this section of the Inner Loop is a walkable street allowing people from the eastern neighborhoods easy access to downtown Rochester. The street is lined with apartment and office buildings as well as some restaurants. Despite the appearance of progress towards revitalizing a neighborhood that was razed for the creation of the Inner Loop there have been some questions and concerns from Rochesterians about whether this project has gentrified the neighborhood. A search of the area on AffordableHouseing.com shows only one listing along this stretch of Union Street, while the cheapest available apartments currently at Vida Apartments and Townhouses, on the corner of Union Street and East Avenue, is $1,015 per month for a studio apartment. This has the potential to price locals out of the neighborhood that these developments are attempting to revitalize. The below map the median income for the city of Rochester from 2013, the year before the project began. Portions of the neighborhood along the Inner Loop East section are below the federal poverty line, which means that some residents may be unable to afford this housing.

However, there is a new apartment building being constructed on the north corner of Union Street and East Avenue by Home Leasing, a local developer. The CEO of Home Leasing, Nelson Leenhouts, described the development project in this way: “We know we are creating a big impact for a diverse group of people with high incomes and people with more modest incomes. That’s good for the city.” The apartments are slated to cost $642-$1,190 per month (studio, 1-bedroom, and 2-bedroom apartments), although it is yet unknown how many of the apartments will fall into the lower end of the price range, as the building is not yet open.

Despite the concerns of gentrification, the apparent success of the Inner Loop East Project spurred former mayor Warren to begin pushing for the infill of the northern section of the Inner Loop, arc four. This section had become the arc with the most concentrated poverty as the northern part of the city was cut off from the downtown business district. In her argument for the removal of this next section, Warren stated, “Connecting the northern part of the city with downtown creates opportunity.”

This second Inner Loop Project is still under consideration, but there has been progress made towards its study phase. In September of this year, Congressman Joe Morelle announced that $4 million in federal funding had been approved by the House of Representatives for the Inner Loop North Project as part of the recently passed Surface Transportation Member Designated Projects legislation. This $4 million, while only a tenth of the total needed funding for the project will be put towards the study, design, and planning phase of the project. Only the future can show whether this second project will be completed and whether the whole of the Inner Loop, once considered the forefront of transportation infrastructure, will be removed in favor of a connected and walkable Rochester.