Rochester’s Subway Line

The twentieth century not only saw the peak and subsequent decline of the railroad in Rochester, but also the development of and disappearance of the Rochester subway system. After the widening and rerouting of the Erie Canal in 1905, parts of its route lay abandoned downtown. This was the case until 1911, when the state decided to sell the right-of-ways of the canal, giving first rights to the cities that they passed through. After deciding to purchase the right-of-way in Rochester, the Chamber of Commerce hired city planners to propose new uses for the land.

What was initially proposed was the construction of an automotive highway. However. Rochester’s leaders felt that this was unnecessary and that a future requiring designated roadways for automobiles was unrealistic. After all, there were only 3,600 automobiles in the whole county at the time. Others proposed using the right-of-way for a street railway service. This was also rejected as Rochester already had an extensive streetcar network. It was eventually decided that the right-of-way would be used to create a subway system and in 1912, City Hall approved $1.8 million for a subway to be called the Rochester Rapid Transit and Industrial Railroad.

The rerouting of the canal began in 1919 and in 1921, after officially purchasing the right-of-way as well as the sections in Greece, Brighton, and Pittsford, the city’s mayor Hiram Edgerton signed the ordinance to begin construction on Rochester’s subway. Construction began in May of the following year to great optimism and enthusiasm from the city’s new mayor, Clarence Van Zandt, who believed that the subway system would only help Rochester’s upward trajectory.

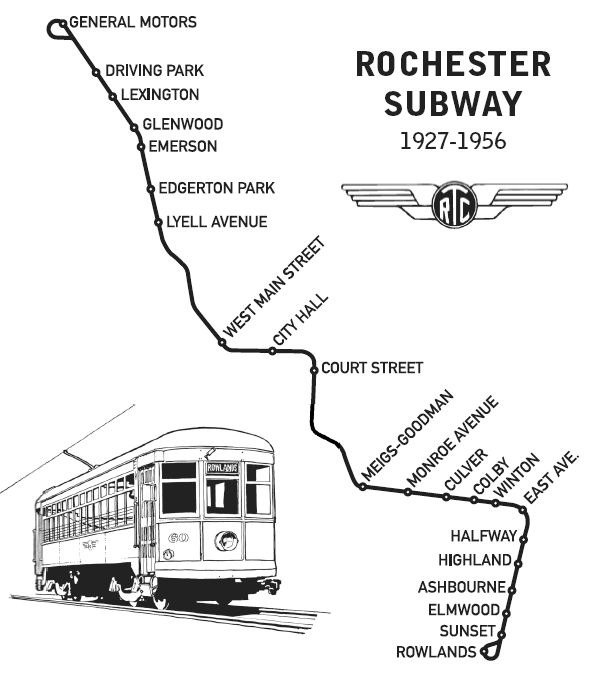

Operated by New York State Railways, a subsidiary of the New York Central Railroad which also operated the streetcars and two of the city’s interurban lines, the subway officially opened on November 30, 1927, although only the eastern end of the line was electrified. The Rochester subway system consisted of only one line that stretched east and west from downtown and despite having over twenty stops, depicted below, only took around thirty minutes to ride from end to end.

The Rochester Subway Line with stations marked on the 1935-36 Plat Map (zoom in to see details)

Like the other forms of rail transit, the subway faced decline and financial collapse in the mid-twentieth century. The start of the Great Depression saw New York State Railways fall into bankruptcy and the removal of all of Rochester’s interurban lines. These lines had been the major reason for the construction of a subway in the first place leaving the subway to be a line through the city with no connections to other modes of transportation. City Hall saw this as a sign and began defunding subway maintenance.

In 1937, however, Harold McFarlin became the Commissioner of Commerce and Railroads and he wasted no time in making efforts to save the subway from collapse. McFarlin began his tenure by purchasing twelve new high speed electric cars and refurbishing all of the stations. He also completed a passenger and freight service to the General Motors plant. Because of his efforts and the new operators of the subway, Rochester Transit Corporation, ridership began to climb for the first time in seven years.

Early 1941 saw the beginning of another decline, however, as Rochester’s streetcars were replaced with buses, removing further connections from the city’s subway line. Ridership dropped again as passengers began to be limited to those who lived immediately along the subway line. Things turned around at the end of the year, with the United States’ entry into World War Two. With the emergency rationing of tires, gasoline, and metal, Rochesterians were urged to use public transportation, particularly the subway, causing subway ridership to enter its peak period, hitting an all time high of over 5.1 million riders in 1947. 1948, however, saw the removal of wartime restrictions causing a boom in automobile use and a steady decline in subway ridership.

Ridership continued to decline as, in 1952, services were reduced. The underperformance of the subway and the increasing number of automobiles in the city prompted New York Governor Averell Harriman to sign a bill that designated the eastern end of the subway line to be converted into Interstate 490 in 1956. By the end of June, the subway was finished with June thirtieth designated as the last day of passenger service and freight service only lasting for another year.

As with the railroad, the continuing evolution of the dominant mode of transportation spelled the end of the city’s reliance on rail-based transportation. The growth in popularity of the automobile and the construction of multiple expressways through the city heralded a new age of transportation.