The Erie Canal

The roots of the land that is now within the city of Rochester stems back to a series of land exchanges following western New York’s incorporation into the United States, the first of which were initiated by Oliver Phelps and Nathaniel Gorham. Known as the Phelps and Gorham Purchase, the two men purchased 6 million acres of land in western New York from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts in 1788. The two investors ran into financial problems from the beginning, mainly due to the land’s relatively unaccommodating terrain for transportation, therefore hindering early commercial investments. After defaulting on their loans in 1790, their land was divided and sold multiple times to different investment groups. The land west of the Genesee River that would later belong to the city of Rochester reverted back to Massachusetts, who then sold it to signer of the Declaration of Independence and the United States Constitution, Robert Morris. This land then was sold to the Holland Land Company.

The eastern banks of the Genesee River saw the city’s first settlement and commercial activity. Phelps and Gorham, before defaulting, sold a 100-acre tract of land near Upper Falls to Ebenezer “Indian” Allen on the condition he construct a sawmill and grist mill by 1789. The area was so remote that after gathering enough labor to build the mills, Allen, with no demand and no influx of settlers in the area, sold it three years later. The land rights traveled through a few different hands before the Pulteney Association, a British investment group, sold the 100-acre tract of land to Col. Nathaniel Rochester for $1,750.

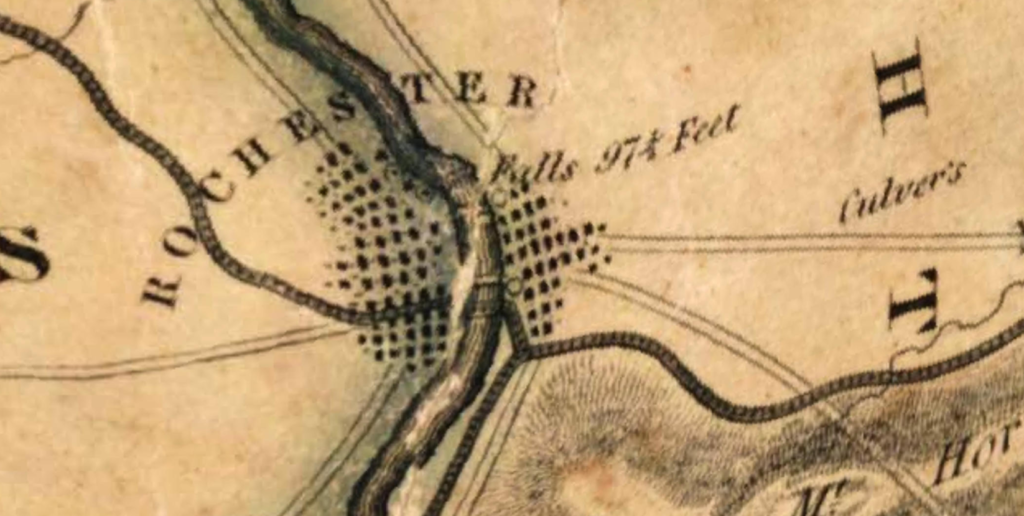

The tract of land’s early development, led by Col. Rochester, centered on the Genesee River’s location and natural characteristics— in other words, waterpower. Rochester and his business partners saw the upper falls as a worthwhile investment. Any goods which travelled up the river would need to be unloaded at the falls and portage fees could be charged. Additionally, the area began receiving an influx of settlers. Newly arrived settlers started to establish small mills along the river. By 1817, the settlement was incorporated as the Village of Rochesterville in 1817 (the -ville dropped in 1823). The County of Monroe 1822 survey map depicts the cluster of flouring and sawmills congregated along the Genesee River, simply labeled “Rochester” as its situated amongst larger rural towns. As mentioned in the introduction, drawing a line around the perimeter the cluster of buildings dotted on the line gives you almost the same circumference as the Rochester inner loop, reflecting the importance of this space along the Genesee River to Rochester’s development.

After the Genesee River’s waterpower brought a modest settler village to the banks of the Genesee, it was the Erie Canal that turned the small village into one of America’s first “Boom Towns.” Though the proportion running through Rochester would be complete in 1823, the 1822 map already showed the anticipated canal route running through the heart of Rochesterville. Before the Erie Canal route was finalized, however, in the region now known as Monroe County, the proposed route was widely contested because it threatened to upend the regional political and economic landscape. The canal’s proposal offered the opportunity to unlock the economic and commercial potential of upstate New York, otherwise bound to transport their raw materials by inefficient roads. The canal sought to link the ports of New York city to Midwest America surrounding Lake Erie. The rural settlers of upstate New York understood the importance of having the canal run through their towns and connecting their rural villages to wider networks of commerce

Before present-day Monroe County was established, the region fell under the two counties, Ontario and Genesee, that would be divided up to form Monroe. During the 1790s, the two county seats, Batavia in Genesee County and Canandaigua in Ontario Country, contained most of the region’s economic activity. When in 1808, New York ordered an official survey of a potential route running east to west connecting Lake Erie to the Hudson River, it was assumed that the canal would run through the heart of these rural towns. However, when news reached western New York that the Erie Canal route was instead being planned to run several miles north of the Old State Road linking Batavia and Canandaigua, townspeople reacted. Gathering in Canandaigua in 1815, rural settlers urged the state to put the canal route through Batavia, Avon, Canandaigua, and Geneva. This route, they argued, already contained a well-traveled road, settled with enough population that a canal could unlock its true economic potential rather than “the relatively unsettled wilderness further north.” This assessment of the region was not unfair either. When Ebenezer Allen built the first mills along the Genesee River in the area, there were constant complaints about “swamp fever,” known as malaria now, and difficulties faced in securing and transporting building equipment and materials through dense forest and swamp.

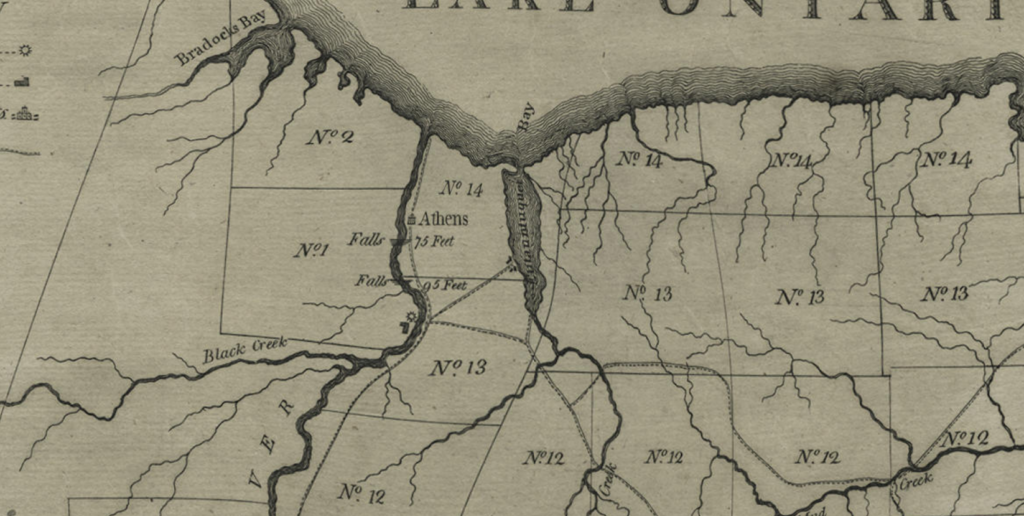

Scanning the Gorham and Phelps 1794 map (below), more than two decades before townspeople lobbied for the canal route through Canandaigua out to Batavia, the cluster of towns in that region and its abundant roads connecting them is apparent. Whereas searching further north, to where Rochester is located today, the map displays a long road running parallel to the Genesee River to a village labeled “Athens” and the two falls along the river are noted.

Canandaigua region

Compared to the sparsely settled “northern wilderness” region

State-level promoters of the Erie Canal, including Governor DeWitt Clinton, already facing pushback from policymakers, asked engineers to find the path of least physical resistance. To avoid a glacial moraine that would require additional locks, engineers decided to curl the canal’s route through Rochesterville.

The economic fate of the region was sealed when in 1823 the Erie Canal opened in Rochester, running over the Genesee River via an aqueduct, where present-day Main Street is. Monroe County was established out of parts of Ontario and Genesee Counties in 1821 when the Erie Canal’s route was finalized. By the mid-1850s, the population of Batavia and Canandaigua remained static around four thousand people, whereas Rochester continually grew to 62,386 in 1860. Rochester became a flourishing city, known as “America’s first boom town” and a gateway city to the west.

The Erie Canal had transformed Rochester, a place formerly too remote to successfully run, support, and operate two mills. Nearly three decades later, by 1834, some 20 flour mills were producing and sending 500,000 barrels of flour to New York City, the same year Rochester received its city charter. At the 1851 World Fair in London, Rochester flour was put on display, receiving international recognition and cementing its legacy as “the flour city.” The Erie Canal’s ability to not only cut transportation times but connect upstate New York towns to national- and international-level ports is what supported the village’s growth into a city.

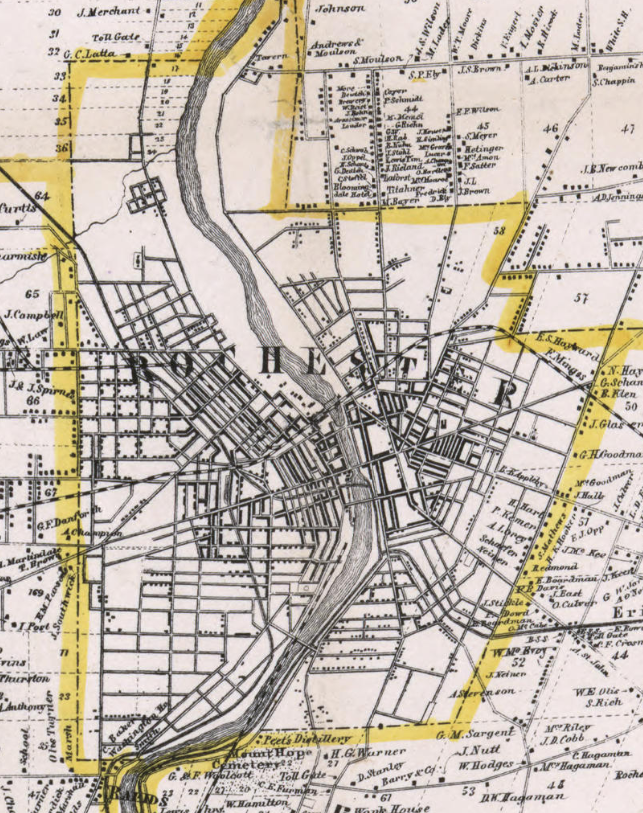

The shift towards Rochester as the regional center of commerce and economic activity was complete. Rochester witnessed an unparalleled amount of urban and economic growth compared to elsewhere in western New York. The heart of this growth? The Erie Canal, of course, perfectly reflected on the 1858 Monroe County map. The map depicts the canal running through Rochester, attached to a feeder canal that ran parallel to the Genesee River connected to the river by present-day University of Rochester River Campus. The thickly congested streets, stark compared to the sparsely settled rural towns outside Rochester, lay right at the intersection of the canal and river. At this intersection, the map also shows the canal crossing the river at a slightly different position, still via an aqueduct, but further north of the former aqueduct.

In 1842, with talks of enlarging the canal, the state allocated money for the city of Rochester to replace its already aging and leaking aqueduct. The city moved the route just north of the original, to where the present-day Broad Street bridge is. The enlargement of the canal and the city’s moving of the aqueduct offers a slight glimpse into the next period of Rochester’s transportation and urban history. Moving into the twentieth-century, national technologies and advancements in transportation threatened to make the Erie Canal, the center of Rochester, obsolete. In response, the canal itself would be reinvented and Rochester’s urban development would be forced to remain dynamic.