The Changing Canal

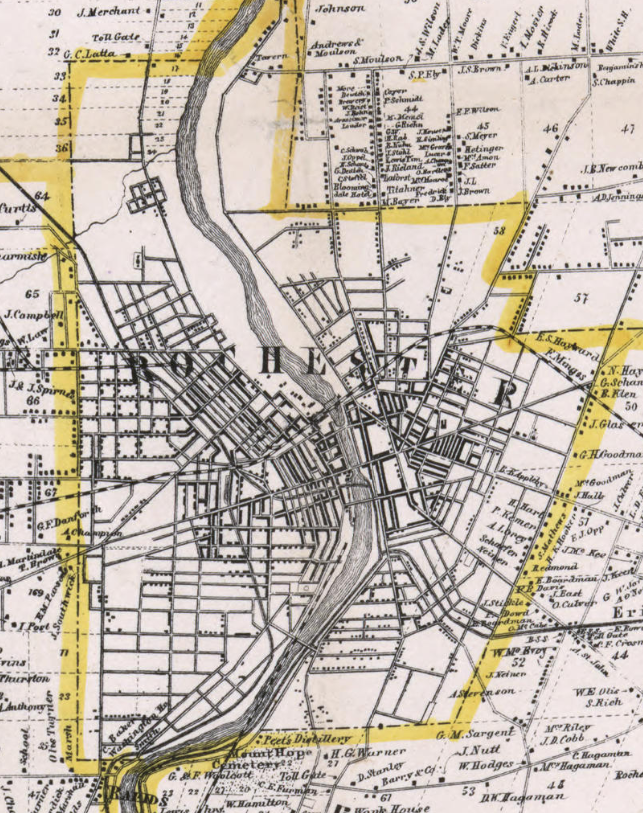

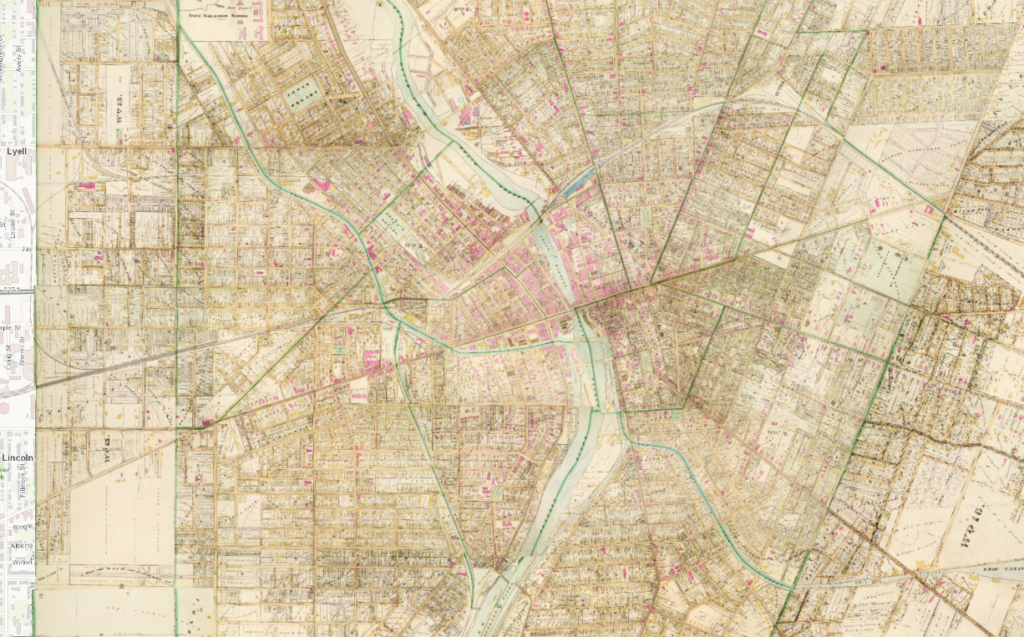

By the mid-1800s, Rochester, a thriving “boom town” thanks to the Erie Canal, was a continually expanding urban city. After its city charter, Rochester began annexing nearby land to accommodate its growing population. Once limited o the confluence of the Erie Canal and Genesee River, Rochester’s economic development and transportation expanded throughout the city. Comparing Rochester’s 1858 map to its 1888 map shows the drastic changes. The cluster of housing and urban space was clearly expanding. However, this growth cannot only be attributed to the Erie Canal, which itself was being reimagined during this period, in fact, this urban expansion of Rochester reflected how the city sought to remain dynamic response to the rapid industrialization of the United States. These outside forces, better technology and means of transportation, forced Rochester to remain adaptive, primarily pushed the city to reroute the Erie Cana and shift economic priorities to consumer products where production did not require manufacturing right on the river or canal. These changes, and how Rochester responded also reshaped the city as an urban space while reflecting the city’s economic priorities. By the early-1900s, the Erie Canal, the foundation of Rochester, became an infrastructural obstacle and secondary concern for the city.

1858

1888

Rochester’s main success from the Erie Canal came from its ability to transport goods and products, mainly raw, to ports and markets. In addition to Rochester’s flour, this also included lumber and other forest products. In the mid-1800s, technological developments, namely the steamboat, and the shifting of raw material markets to untapped regions as those resources in upstate New York dried up forced Rochester to be dynamic to continue its urban growth. Additionally, the consolidation of several upstate New York railroads diluted the commercial activity across interior upstate New York while the Ohio and Mississippi River Valleys outcompeted the commercial network linked by the Erie Canal. Rochester investors shifted attention to consumer products. Kodak was founded in 1892, Bausch & Lomb in 1852, and Western Union in 1851, represented this shift along with dozens of other breweries, clothing manufacturers and machine tool factories that spawned during this post-Civil War era in Rochester. The spatial change of economic development outside the banks of the Genesee River and Erie Canal can be attributed to this shift as electricity, not water or steam, powered the manufacturing processes of these companies.

Rochester was not the only one keen to remain competitive in a nationally and globally shifting market, New York State pondered ways to reinvent the Erie Canal, and other canal systems in New York. Supported by then-governor Teddy Roosevelt, the state sought to dramatically expand the Erie Canal, and other canal routes in the state, and combine them into one large statewide Barge Canal system. The upgrades would include modern cement, electrically powered lock systems, and the inclusion of tugboats to replace animal power. The canal’s capacity would increase from 250 tons to 3000 tons. The proposed size of the barge canal meant it had to be rerouted in certain sections, including bypassing urban downtowns that the existing, smaller, canal drove through. These included Syracuse, Buffalo and Rochester.

In Rochester, a city which can thank the placement of the Erie Canal for its development as a city, used the canal’s transformation into a Barge Canal as an opportunity to decenter it as a focus of economic development and transportation.

Unlike the relocation of the downtown Rochester Erie Canal aqueduct from Main Street to present-day Broad Street for engineering purposes, the rerouting of the canal, as it transformed into the New York State Barge Canal, reflected deeper economic meaning. Rochester no longer relied on a canal as the downtown and commercial center or transportation hub. Instead, the city reimagined their downtown urban space, dominated by emerging transportation technology, railroads, subways, and eventually the automobile. Yet, these new technologies used the same physical space that previously was occupied by the Erie Canal. The physical reuse of the same space is most likely because city planner, amidst a dense growing city, were short on space to incorporate new infrastructure. However, the space being reshaped from canal to railroad (and later highway as discussed in the fourth part) demonstrates how this space continued to be center for the city’s growth. A space able to adapt to Rochester’s needs as they sought to remain economically competitive and connected in a nationally growing market.

Below is a comparison of downtown Rochester, where the space and route of the canal continues into 1935, but instead of water, it is the metal and cement of rail lines, discussed further in the next section. The red line is the original Erie Canal route going over present-day Main Street, the orange line is the route after the canal’s initial expansion.

Rochester city planners and legislation began designing the new route of the Erie Canal, where it would then be included in the statewide Barge Canal system, in the early-1900s. From the beginning, city officials wanted to pivot the canal before the city lines, towards a new conjunction with the Genesee River several miles south of the original crossing, cutting through Genesee Valley Park. For the last factor, the plan faced staunch opposition from the public who disagreed with cutting the Olmstead-designed Park, opened in 1888 and just under twenty years old at the time, in half. As a compromise, city officials hired landscape architects and engineers to construct Olmstead-inspired pedestrian bridges that would connect the park, several which are seen below on a 1935 Rochester map.

The Barge Canal system, though heavily pushed by Teddy Roosevelt and other state policymakers, was never meant as a long-term economic plan. Its initial goals were to keep the canal system somewhat relevant, even if on a regional scale. However, the Barge Canal would only get approved, and most of its construction complete, during World War I when rail lines were congested and transportation times for domestic materials and goods decreased. A canal system capable of holding large barges with full cargo helped elevate some of the pressure on other transportation systems in the eastern United States.

The rerouting of the canal out of downtown Rochester did not only signal the change in the history of Rochester’s urban development but also the cultural use of the canal as a space. Since the end of the war, the canal system has been used primarily by recreational traffic. In Rochester, most of the Erie Canal is paralleled by multi-use paths, there are facilitates to either pay for a boat trip or put in your own kayak, or boat, on the canal itself. As a space, the canal is no longer a place that represented the economic advancement of the United States, or even western New York. By the end of the 20th century, with less than 100 cargo trips per a year and most of the canal throughout New York established as a National Heritage Corridor by the state and national government, the Erie Canal cemented its purpose and use as a recreational space.

As for downtown Rochester and the city’s urban development, the space previously occupied by the Erie Canal would be transformed. As the city sought to be commercially and economically competitive, it had to reimagine its downtown as a space fit for the twentieth century.